Genomic Sequencing and the Omicron Variant

Rob Thomas

Final Project for ITEC 740, Fall 2021

Header image: screenshot of "Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus - Global subsampling" from NextStrain on 12/6/22. Omicron in red.

Disclaimer: I am not a scientist. I am a social theorist with expertise in the relationship between zoonotic pandemics and language. Here, “language” means: discourses, stories, ways of speaking, ways of seeing, forms of visualization. This includes apparatuses: social mechanisms, institutional arrangements and how these work, together, with discourses or narratives to make empirical social meaning.

Introduction

For my culminating project in ITEC 740 (Computer Design of Instructional Graphics), I will look at current data about genomic sequencing and the Omicron variant of SARS-COV-2. This educational experience is designed to promote engagement because we still don’t know a lot about the Omicron variant and the pandemic is something we are all still living through. This project will likely NOT be updated after my presentation is given on Dec. 8th. It will, thus, provide a snapshot of a moment in time in the life of the pandemic.

This use of data visualization to think seriously about the epidemiology of the Omicron variant of COVID-19 will be placed in the historical context of the genomic sequencing of an earlier zoonotic pandemic, HIV/AIDS. This will provide much needed historical context for our discussion. Terminology such as “zoonosis” and “reverse zoonosis” will be defined below.

I encourage you to think of this presentation as a detective story that won’t be solved by the time we meet this Wednesday. But many of the mysteries may well be solved in the coming weeks or even days ahead. My hope is that this makes our work together both more challenging and more exciting.

I also hope to show that empirical data and genomic sequencing often tell us a completely different, but more accurate, story about viruses than the ways we speak about and see viruses socially.

Scientific Resources on Covid-19

Below are some scientific resources I’ve found useful in following the story of this pandemic.

- CIDRAP Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. University of Minnesota. This is a great resource that is frequently updated, including links to pre-print (pre peer-reviewed) medical research.

- MedRxiv The Preprint Center for Health Sciences. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, BMJ, Yale University. This links to medRxiv’s pre-print (pre peer-reviewed) articles on COVID-19.

- NextStrain Real Time Tracking of Pathogen Evolution, discussed below.

- Eric Topol. Dr. Topol’s articles, research and Twitter feed have provided some of the most valuable, up-to-date scientific information during the pandemic.

- Trevor Bedford. Trevor Bedford was one of the first scientists to track community spread of COVID-19 and is a partner with NextStrain, discussed below.

How to Talk about a Virus

Image above: screenshot from Heather Murray, “Fearing a Fear of Germs: How Did the Surgical Mask Transform from a Sign of Bigotry to a Sign of Care?” Historians.org

When talking about viruses, it is important to make a distinction between the empiricism of the virus and the empiricism of what we are doing when we speak about and see viruses socially. These are two distinct and entirely different things, yet both add to our knowledge about the pandemic and how it affects us. Both affect us a great deal and, as we know, both can kill us.

1. The Empiricism of the Virus.

2. The Empiricism of the Social Apparatuses Surrounding the Virus. (If it’s easier, you can call these the “narratives,” but these narratives have real, material effects that we can trace out or map as they flow through social and institutional arrangements.)

People make a lot of mistakes by not paying sufficient attention to this distinction or by paying attention to one aspect of this two-fold nature of the virus at the expense of the other. But to understand what the virus is doing to us as a virus and what it is doing to us socially, we need to include both. We need to properly grasp both of these ways of making meaning to fully understand the pandemic. And, obviously, society doesn’t fit in a test tube, so our stories about this second way of thinking are still going to be . . . stories. They are going to be something we’ve created (but that we have to try to give as accurate an account of how we have created those stories as we possibly can).

On apparatus, see Giorgio Agamben, What is an Apparatus? (Stanford UP), 2009.

What is Zoonosis?

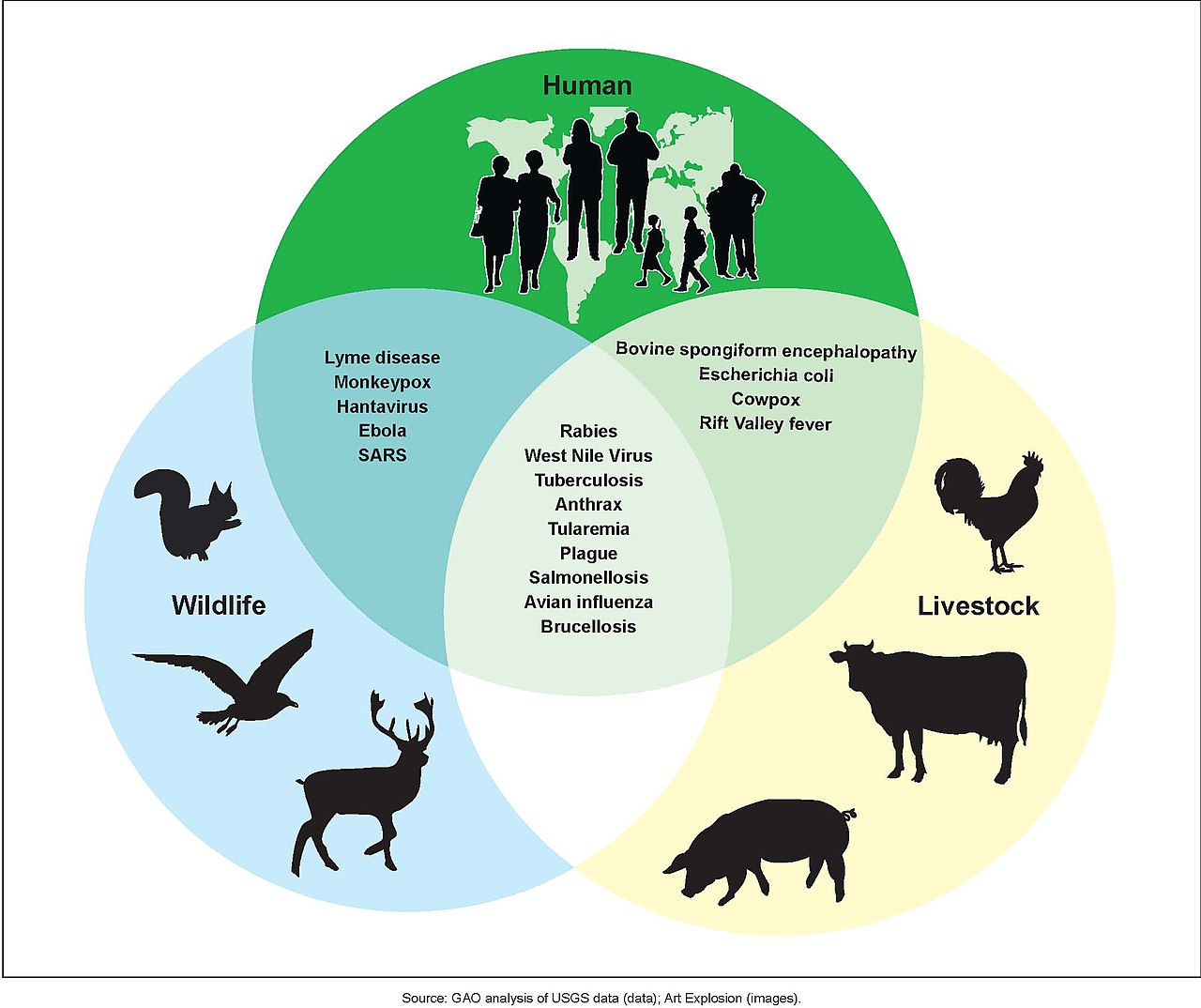

Image Source: Wikipedia, “Zoonosis”

Zoonosis is the term we use to describe viruses jumping from animal hosts to human hosts. The current (tenuous) scientific consensus is that SARS-COV-2 jumped from bats to an intermediary animal (possibly raccoon dogs) to humans at some point prior to the current outbreak in late 2019. This is not yet a scientific fact because we haven’t definitively proven the origins of the virus, but it remains the most likely scientific hypothesis based on the data we have to date.

HIV is also a zoonotic pandemic, making the jump from chimpanzees to humans in Africa in the early 20th century due, mostly likely, to the trade in animal meat.

Zoonotic pandemics are the result of globalization (aka colonialism, industrialization, etc.). They are effects of the era we call the Anthropocene.

Anthropocene defines Earth's most recent geologic time period as being human-influenced, or anthropogenic, based on overwhelming global evidence that atmospheric, geologic, hydrologic, biospheric and other earth system processes are now altered by humans.

The word combines the root "anthropo", meaning "human" with the root "-cene", the standard suffix for "epoch" in geologic time.

The Anthropocene is distinguished as a new period either after or within the Holocene, the current epoch, which began approximately 10,000 years ago (about 8000 BC) with the end of the last glacial period.Encyclopedia of Earth

The Anthropocene Epoch is an unofficial unit of geologic time, used to describe the most recent period in Earth’s history when human activity started to have a significant impact on the planet’s climate and ecosystems.

National Geographic Encyclopedia

Increasing economic development and technological progress have come at a tremendous cost to the planet. As humans encroach further on areas inhabited by animals and as we become globally interconnected, this dramatically increases the possibilities for zoonotic events. Global warming only accelerates this process. We should expect more zoonotic events in the coming decades.

Genomic Sequencing and HIV

Photo: “Part of DNA sequence – prototypification of complete genome of virus,” from Wikipedia.

Genomic sequencing has only recently revealed that the epidemic of HIV/AIDS in North America was initially seeded in 1970 via the Caribbean. The initial cluster of HIV cases among men who have sex with men in the U.S. took place in NYC in roughly 1972. This cluster, in turn, lead to a second cluster of cases in San Francisco, another outbreak, in roughly 1978. In other words, the cluster in SF in 1978 emerged via an ancestor of the cluster from 1972. These two viral seeding events lead to the first cases of illness among men who have sex with men that wasn’t detected until the spring of 1981.

Recent genomic research has shown that the incubation period for HIV can be as long as 10 years. By the time men who have sex with men first started to become ill with HIV/AIDS in 1981 (and even much later in the 1980’s and early 90’s), they had long since already been infected with the then unknown pathogen.

See Michael Woroby, Thomas D. Watts, Richard A. Mckay, Marc A. Suchard, Timothy Granade, Dirk E. Teuwen, Beryl A Koblin, Walid Heneine, Philippe Lemey & Harold W. Jaffe. “1970’s and ‘Patient 0’ HIV-1 genomes illuminate early HIV/AIDS history in North America,” Nature, 26, October, 2016. Free version available at: https://tinyurl.com/wn3kp49n.

Most of our ways of talking about HIV/AIDS do not include, nor account for this information. This is knowledge that we now have, thanks to genomic sequencing. From popular media to everyday speech, there are certain moralisms and forms of policing that still pervade our discourses about HIV/AIDS. These ways of thinking are dispelled by this new knowledge. Yet few people know about this new genomic data.

Below: Timeline of HIV Spread in North America Based on Genomic Sequencing. MSM refers to men who have sex with men.

1970 — Initial Seeding of HIV in NYC from the Caribbean.

1972 — Initial Cluster of HIV infection in NYC among MSM.

1978 — Second Cluster of HIV infection in SF among MSM.

1981 — First Cases of Illness Reported Among MSM from the Initial Clusters of Infections.

What is the Omicron Variant of Covid-19?

Evolutionary virologists were largely expecting Delta Plus to be the next worrisome variant.

— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) December 6, 2021

Instead we got Alpha, Beta, and Gamma Plus🤯 pic.twitter.com/HcUAQ1ZWeb

The Omicron variant of COVID-19 is the same strain of the virus that was circulating, globally, in the summer of 2020. Only that strain or those strains have emerged a year and some months later in heavily mutated form. One of the questions this poses for us is: how did the virus get so heavily mutated and where, exactly, did these mutations take place? In another section of this presentation, below, we will look at three of the current hypotheses surrounding this question. I promised you a mystery, a detective story, and this is it.

As of Sunday, 12/5 (continuing to 12/7), the media narrative has been about reduced severity of illness in Omicron, but as Eric Topol and others have pointed out, we just don’t know if that is the case due to a lack of data, specifically about people over 60. Omicron seems to be showing up in younger populations in South Africa, which is, in turn, translating to mild illness. We do not yet have data about how it is affecting older populations of people. Narratives about reduced severity for Omicron are currently premature. Read Topol’s entire thread, embedded below, for more on this issue.

Does Omicron lead to less severe illness than prior variants ? We don't yet but let's review what is the basis for the hope /1https://t.co/hyEWWNsO3q pic.twitter.com/wM0L2ySZWy

— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) December 7, 2021

The question of possible increased transmissibility of the virus and whether or not it leads to more severe illness than previous variants is currently being tracked. Transmissibility, as currently charted is much higher than all previous variants, as can be seen in these charts below that show the spread of Omicron in Gauteng province South Africa. Omicron is the one on the left going straight up. Suliman’s entire thread is worth reading for much needed context (i.e. how to properly read this chart). Note: the chart has already been manipulated to spread misinformation. This is Suliman’s chart. Only refer to his work and not to others spreading fake versions of it.

Different versions of this graph showing 7-day rolling avg #COVID19 cases in Gauteng floating around. For those interested, here's the latest update tonight:

— Ridhwaan Suliman (@rid1tweets) December 5, 2021

Will share an analysis, including a look at hospitals and deaths, as soon as I get a chance..#Omicron #Gauteng #4thWave pic.twitter.com/w2VWcsmLkl

In the coming days and weeks we will get much more definitive answers about transmissibility and disease severity.

How to Use NextStrain to Track Genomic Sequencing of Covid-19 in Real Time

Video: "Introducing Nextstrain" (3:36)

Three Hypotheses about the Origins of the Omicron Variant

There are three hypotheses about the origins of the Omicron variant. Remember, this is, genomically, essentially the same variant or variants circulating in the summer of 2020, but with a large number of mutations. These hypotheses are trying to account for what happened. How did the strain(s) from the summer of 2020 suddenly re-emerge with a large number of mutations?

The three current hypotheses are:

- 1. The variant circulated and mutated in an isolated group of people which then infected a more populous area.

- 2. The variant mutated in an individual who had a weakened immune system, such as a person with HIV.

- 3. The variant is the result of reverse zoonosis. This means the virus jumped from humans to another animal, mutated in that animal, and then jumped back to humans in the fall of 2021.

It’s important to point out that we know Omicron was circulating (more than likely elsewhere) before it was first reported in South Africa. We don’t yet know where it came from.

The HIV hypothesis is based on an earlier patient in South Africa who had an untreated HIV infection and, thus, was immunocompromised when they became infected with SARS-COV-2. The patient was observed for 6 months, with scientists being able to monitor and document the significant mutations taking place as the patient (initially, over a 6 month period) failed to fight off the infection.

There’s some early—too soon to know—data on the possibility of a reverse zoonotic event for the origin of Omicron. Waste water surveillance in NYC has detected mutations similar to Omicron in what scientists believe to be non-human feces. These are speculated to be from rats. The hypothesis is that the virus went from humans to rodents, mutated, and then jumped back from rodents to humans. A process of reverse zoonosis. This thesis is also strengthened by the finding that animal species such as white tailed deer have been harboring the virus for some time now.

It’s important to say that all of this is speculative and we just don’t know. We don’t have any hard answers for any of these questions yet. I believe we will eventually have solid answers about the genomic origins of Omicron because of our previous ability to trace historical aspects of the HIV epidemics in the 1970’s using genomic sequencing.

Conclusion

Thank you so much for following me on this journey into the story of genomic sequencing, COVID-19, and the Omicron variant. This was a challenging topic to choose, from the hard science and data, to the creation of all of the interactive elements that I built for this web page. I hope you found this work useful to you in some small way. My learner is a student in an advanced degree program at an institution of higher learning. The idea was to create an educational experience that fostered engagement due to the subject matter, which remains urgent and timely, to share some complex information in a relaxed manner and to include a lot of different visual imagery, as well as interactive content to engage the learner. I wanted to allow my learner to come to their own conclusions about what I was sharing with them. I think, with science, it’s important to be open to what we might discover in the very near future about where this pandemic is headed because it’s constantly surprising us. A significant part of the story of this pandemic, however horrific, is a fascinating mystery. And the answers to the questions we don’t know right now with regard to the Omicron variant, which I am confident we will soon get, are important to all of us.

Update: 12/8/2021, 11:01 AM C.S.T.

I forgot to include the recent study that showed that Omicron had picked up a part of a coronavirus that causes the common cold. You can read the pre-print study (not yet peer-reviewed), here “Omicron variant of SARS-COV-2 harbors a unique insertion mutation of putative viral or human genomic origin.” This research is important to the story of how Omicron has become more transmissible. It has picked up a piece of a completely different coronavirus. One that causes the common cold.

Two significant pre-print studies were posted this morning:

I have not had time to review the first of these studies, but I have quickly scanned the latter (due to it’s alarming title). Be sure to read the full analysis for further clarity (i.e. it suggests that there is vaccine escape—meaning Omicron beats the Pfizer vaccine—with two doses but that three doses provides protection). The questions this further raises are: how robust is this study and what can be inferred from it given its small sample size? If a third shot of Pfizer provides some protection, how much protection does it provide and for how long?

One important, and hopeful, thing that I’ve left out of this presentation is that prior to the emergence of the Delta variant in the West, scientists were working on a pan-variant vaccine. That means a vaccine that would target all variants of the coronavirus and, effectively, all coronaviruses. This would be something along the lines of a proverbial cure for the common cold. Prior to Delta, scientists were confident in their ability to eventually create such a vaccine. Their hope was that the initial vaccines, which were produced to target earlier variants of SARS-COV-2 and not Delta, would buy them enough time to do so. The epidemiology of the Delta variant, which wasn’t clear to scientists until July of 2021, stunned the scientific community. Omicron is now delivering a one-two punch. In a recent Twitter thread, Eric Topol asks: what happened to this push for pan-variant vaccines and why aren’t we fast tracking them? See his comment in the embedded Tweet below. Note the date of his Tweet is November 26, which seems like a lifetime ago in tracking Omicron.

From Omicron's sequence, there's a lot of antigenic drift, posing the threat of evading our immune response. Good that vaccine companies are gearing up for it. But we ought to be pressing hard for a pan-sarbecovirus vaccine that would target *all* variants https://t.co/avBeceJvox

— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) November 26, 2021

References

Agamben. G. (2009). What is an Apparatus? Stanford UP.

Bedford. T. (2021).

https://twitter.com/trvrb.

Twitter. Accessed December 6, 2021.

Cele. S. et. al. “Omicron has extensive but incomplete escape of Pfizer BNT162b2 elicited neutralization and requires ACE2 for infection.” MEDRXIV.

Encyclopedia of Earth. “Anthropocene.“

Accessed December 6, 2021.

National Geographic Encyclopedia. “Anthropocene.”

Accessed December 6, 2021.

Topol. E. (2021).

https://twitter.com/EricTopol.

Twitter. Accessed December 7, 2021.

Venkatakrishnan, A., Anand, P., Lenehan, P., Suratekar, R., Raghunathan, B., Niesen, M. J., & Soundararajan, V. (2021, December 3). “Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 harbors a unique insertion mutation of putative viral or human genomic origin.”

Wilhelm. A., Widera. M., Grikscheit. K., Toptan. T., Schenk. B., Pallas. C., Metzler. M., Kohmer. N., Hoehl. S., Helfritz. F.A., Wolf. T., Goetsch. T., Ciesek. S. (2021, December 8). “Reduced Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant by Vaccine Sera and monoclonal antibodies.” MEDRXIV.

Woroby. M., Watts. T.D., Mckay. R.A., Suchard. M.A., Granade. T., Teuwen. D. E., Koblin. B.A., Heneine. W., Lemey.P. & Jaffe. H.W. (2016, October 26).

“1970’s and ‘Patient 0’ HIV-1 genomes illuminate early HIV/AIDS history in North America,” Nature.