Those who are truly contemporary, who truly belong to their time, are those who neither perfectly coincide with it nor adjust themselves to its demands. They are thus in this sense irrelevant. But precisely because of this condition, precisely through their disconnection and this anachronism, they are more capable than others of perceiving and grasping their own time … Those who coincide too well with the epoch, those who are perfectly tied to it in every respect, are not contemporaries, precisely because they do not manage to see it; they are not able to firmly hold their gaze on it

—Giorgio Agamben, “What is the Contemporary?

1. The Problem 1. The Problem

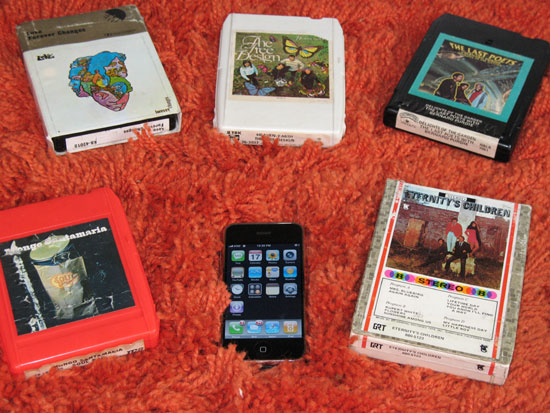

The problem of this instructional design learning theory demo is: How do we think the historical present? What is the history of the present? How do we think about a period of time that we are all—always and already—in?

Image: The iPhone 1.0 surrounded by its future (8-track tapes on shag carpet). Photo by the author (2007).

2. The Learner 2. The Learner

The learner for this demo is an undergraduate college student in a junior level (i.e. upper division) humanities course on history and culture.

Image: Occupy SFSU. Photo by the author (2011).

3. The Objective 3. The Objective

The object of this learning experience is to get students to begin to think historically, without being “historicist,” based on their own life experiences. The distinction between historicist and historical thinking is exemplified by what we were able to do or study historically before the riots for ethnic studies at SF State—historicism, the way things “really were” according to the then present order of things—and what we were able to do afterward—which is a people’s history, a history of women, a history of people of color, a history of post-colonialism, a history of gender, a history of sexuality; a history of everything that was excluded from, or written out of, historicist thinking.

4. The Instruction 4. The Instruction

For our next class, write down a list of the significant events in the world that you feel have shaped your own life, the time you live in, and that define your era. Try to list at least 10 events.

There is no right or wrong way to do this exercise.

Bring the list with you to class.

In the next class session we will form groups of 5 that will enable you to discuss your lists with each other for 50 minutes. Talk about your list with your peers, including why and how these events have shaped your own life. Each person in the group should have at least 10 minutes to slowly go over each event on their list and its impact on their own lives. Take your time. Feel free to ask questions of each other and learn from your peers. These events, including their meaning and impact on our lives, are not easy to unpack.

I will check on each group as your discussions are taking place.

I will also write down my own list of 10 events and bring it to class to share with everyone.

After your group discussions, we will have a larger classroom discussion about the events that we felt shaped our lives (including the whys and the hows). This larger class discussion will further enable us to learn from each other. What, collectively, do these events that have shaped our lives teach us about what we call the present?

Image: Ocean Beach, SF (April, 1975). From The Cliff House Project.

5. The Learning Theory 5. The Learning Theory

How is this a constructivist learning example?

1. The question or problem to be solved is one for which there can be no answer.

2. How can we think about the historical present (i.e. how we got to where we are now; also, where are we now)?

3. The problem is broken down into a list of 10 events which each learner constructs based on the impact of these events on their own lives. The learner is constructing a map of how they think about the era in which they live through this activity.

4. The answer will be different for each person. Each person will (effectively) construct their own map of the historical present based on their experiences of it.

5. The learner will then approach this problem together within the group, sharing their lists and the hows and whys of them.

6. The group does not impose a uniformity of answers—usually typical of group work—but returns differences and similarities in response. (Overlap is built into the learning experience.) The group problem solving enables them to see similarities and differences within their responses and learn from the varied and diverse experiences of their classmates.

7. The collective accumulation of answers to this problem will inform a larger answer to the question/problem posed, and allow the learners to move forward in productively studying other historical eras in relation to their own. (It gives them something to work from.)

8. The teacher is a facilitator and a participant in this experiment. The teacher is also constructing a list of events and adding their own bits and pieces to the larger construction that the class makes, without subsuming what the students construct.

9. Assessment and feedback come in the final discussion. We do check what we’ve all learned, collectively and individually, by the end of the class.

10. Scaffolding is provided in this case by first walking students through a reading assignment on the problem and facilitating the exercise. Normally, scaffolding is a long, slow build for me. This activity worked perfectly as an introduction to problems centered around thinking historically.

11. There was an essay prompt handed out later about this activity (see below) that added significantly to the students’ learning experience.

Image: Seawall (with steps covered in sand due to erosion), Ocean Beach, SF, by the author (2010).

Conclusions: Context Conclusions: Context

My goal as a teacher was to get my students to begin to think historically (without being historicist) based on their own life experiences. I had never done this learning activity before and it was a last minute decision. I handed out this assignment on the first day of class and had the students bring their lists to the second day of class. It was a great experience for everyone and a wonderful way to begin the semester. As part of their first essay assignment, I included the following question (from among two they could choose from—they all chose this question!):

Essay Question: Using your own list of 10 events that had an impact on your life, compose a 2 page reflective paper. (I also had them include a citation from one of the critical essays assigned.).

I really loved doing this and will use it again if I am ever assigned to teach this type of course.

I am honestly shocked at how much this learning experience aligns with constructivst theories. The minute I started reading about constructivism, I thought about this activity. In the real-world case example of this class, I was very fortunate. Normally, my courses are very large. This course had 7 students in it. So, we didn’t break up into groups, our class was a group, and this also helped the exercise (I was the facilitator of the group and it lasted for 70 minutes). If I were to do this in a larger class I would absolutely use the group method.

References References

Giesen, Janet. (No Date). Constructivism: A Holistic Approach to Teaching and Learning. [PDF file]. Retrieved from iLearn for ITEC 800.