1. Thinking With Shoes

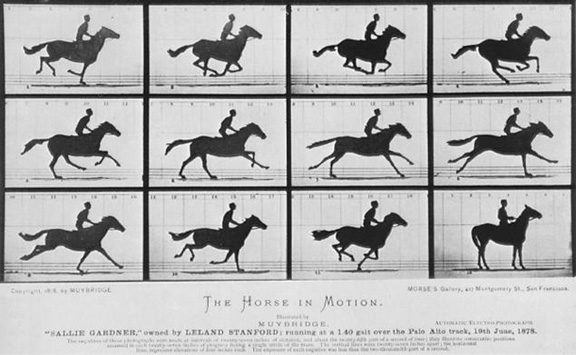

I was recently reminded of Liam Kyle Sullivan’s 2006 electro-clash, viral video, “Shoes.” I was teaching the work of photographer and inventor Eadweard Muybridge. My students and I were discussing the massive technological changes that marked the 19th century, variously described as, the “annihilation of time” (Marx) and the “annihilation of space” (The Philadelphia Ledger on the invention of the telegraph, also known as “instantaneous communication”). Suddenly, people who had marked their daily lives for centuries—including their work day—solely by the sun rising and the sun setting—were thrown into an entirely different world. One that marked time in a completely different, more disciplinary and hyper-disciplinary, way. I asked my students how they marked their work days? I also helpfully pointed out that when they were on social media, they were also “working” (for whomever owns the social media platform you happen to be “on”). Is there even any “time,” anymore, when we are not working? Is this not one of the hallmarks of our own era of hyper-instantaneous communication?

I asked my students to think about the role that technology plays in their everyday lives. And, then, for some inexplicable reason, there it was. The incessant and joyful beat of “Shoes” just popped into my head.

"Let's get some shoes." Frame grab from "Shoes" by the author.

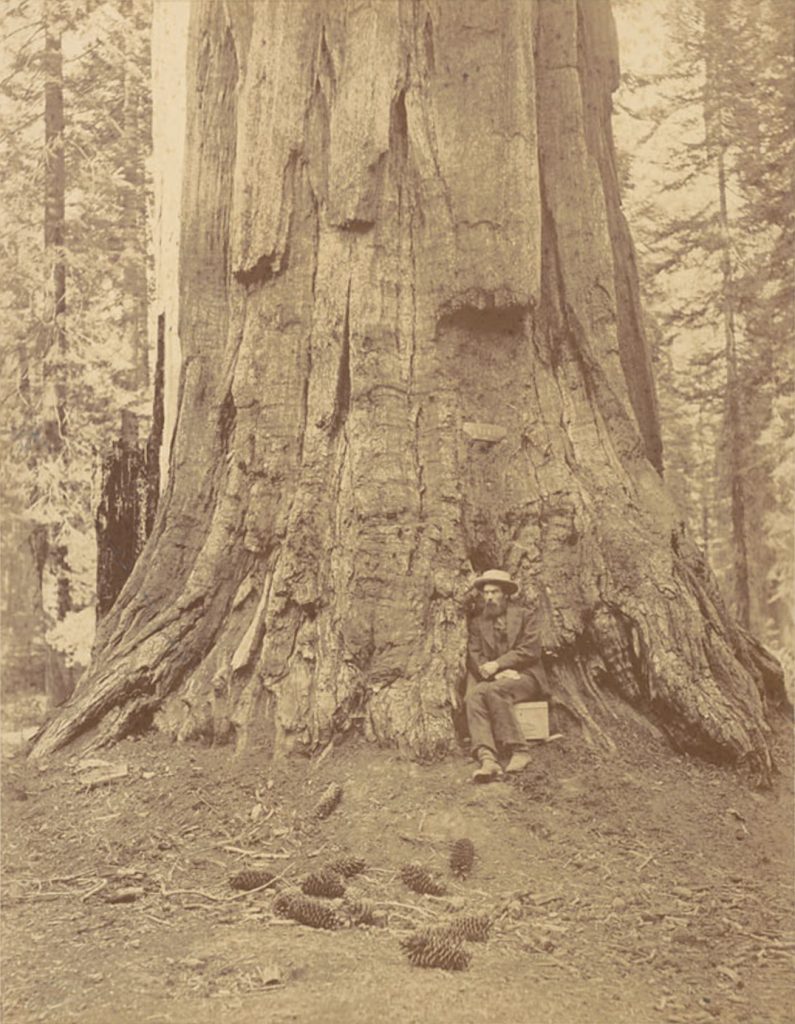

Albumen silver print photograph of Muybridge in 1867 at base of the Ulysses S. Grant tree "71 Feet in Circumference" in the Mariposa Grove, Yosemite, by Carleton Watkins (Source: Wikipedia, public domain)

Muybridge, "The Horse in Motion" (1878)

Animated gif of Muybridge photos (these began appearing on the web circa 1996)

"Stupid boy." Screen grab from "Shoes" by the author.

Video: Liam Kyle Sullivan, "Shoes" (2006)

2. Post-cinema and “Shoes”

My sense of the “post-cinematic” comes first of all from media theory. Cinema is generally regarded as the dominant medium, or aesthetic form, of the twentieth century. It evidently no longer has this position in the twenty-first . . . what is the role or position of cinema when it is no longer . . . a “cultural dominant,” when it has been “surpassed” by digital and computer-based media?

Steve Shaviro, "What is the post-cinematic?"

The concept of post-cinema points to the ways we increasingly experience and make media in multiple, dispersed, digital and networked forms (and how, in turn, this affects and “makes” our subjectivities). Not only do you likely not watch most of your media in the form of cinema or at a movie theater, you watch media on various digital devices. You don’t just watch—to take a singular example—The Walking Dead, you also watch the television show about The Walking Dead. Moreover, you don’t just watch the show and the show about the show, you read the comic book that the show is based on. You, also, don’t just read the comic book, you read blogs and social media posts about the show or about the comic, etc. Moreover, you play any number of video games based on The Walking Dead. And, also, read blog posts or watch videos about the video game. This is just one of many examples that illustrate how the media regime of the early 21st century is dramatically different from other eras.

Trailer for Richard Kelly's Southland Tales (2006).

In his book Post-cinematic Affect (2010), Steve Shaviro cites various examples of what he calls the post-cinematic media regime, from Grace Jones’ music video, “Corporate Cannibal” (2008) to Neveldine and Taylor’s film Gamer (2009). But perhaps the best example can be found in his reading of Richard Kelly’s often derided 2006 film Southland Tales. A film that stars one of our greatest living actors™, Justin Timberlake. As Shaviro writes: “The film bathes us in an incessant flow of images and sounds; it foregrounds the multimedia feed that we take so much for granted, and ponders what it feels like to live our lives within it (67).” Shaviro, ultimately, argues that the film got something right about the world we live in, today, without our quite noticing it, at the time.

2006 is also the year that “Shoes” broke.

Viral is . . . I don’t know. I guess there’s a recipe for it, but I couldn’t tell you what it is.

Liam Kyle Sullivan, "Ten Years of 'Shoes”"

"Fuck you!" Frame grab from "Shoes" by the author.

I suppose “Shoes” popped into my head because I remembered reading an interview with Liam Kyle Sullivan (referenced above) several years ago and it struck me as interesting that he had no idea how to make a viral video, much less how to replicate the success of “Shoes.” Also, I think that “Shoes” is just a really sweet example of what a post-cinematic world feels like. Totally justified teenage (minor subjective) rebellion that revels in “getting what it wants,” which, of course, happens to involve shopping incessantly for shoes, and then screaming “fuck you,” over and over after numerous men have told you they think you have “too many shoes,” and “this style runs small, I don’t think you’re going to fit.”

As you can guess, this instructional demo uses “Shoes” as a way of getting students to think about media in a post-cinematic world. Why do (or did) we like “Shoes?” What can “Shoes” teach us about what makes a viral video “happen” ?And what about post-cinema?

3. Learning Activity

Note: This will be revised, condensed, etc. before it reaches my learners.

1. Watch the Video “Shoes.”

2. Take notes about the video. Anything that comes to mind.

3. How does this video make you feel?

4. Do you remember this video? What do you remember about it, including the social circles in which you shared it?

5. Why do you think this became one of the very first viral videos?

6. Watch the video again.

7. Draw a “map” or diagram of the various parts of the video.

- a) What is the narrative structure of the video?

- b) What are the formal properties of the video (how was it made)?

- c) What kind of techniques are used in this electro-clash video?

- d) Think about all of these different elements, from the narrative, to the music, to the staging of the video.

- e) Do your best to map out a rough diagram of these elements (for yourself).

8. After doing all of the above, how would you answer Liam Kyle Sullivan’s question? How or why do you think “Shoes” became a viral video?

9. What does “Shoes” have to teach us about the concept of post-cinema?

Using your notes, and taking everything from the above exercise into consideration, write me a 2 page paper about “Shoes” and post-cinema. Be sure to cite Shaviro in your paper.

[Note: This learning activity will be broken up between a classroom activity, in which students share their own research about “Shoes” following the rubric above. The 2 page paper question will be one option among others for writing a required 2 page paper on the concept of post-cinema.]

4. Assessment

How is this an example of the use of a cognitivist learning theory?

It certainly grabbed my students’ attention the minute I started talking about “Shoes” in my class. An old, weird inventor, photographer, and murderer from the 19th century is really no match for the power of “Shoes.” The same thing happened when I talked about “Shoes” that same night in my Emerging Technologies class. People got excited and even wanted us to all watch “Shoes” in class.

It’s also affective. This learning experience is fairly typical of the kind of “choose-your-own-guided-adventure” I try to allow my students to have.

The point is to connect something we are learning about in this class I am teaching—a fairly big concept called post-cinema—using the everyday lives of my students (and myself) because we all share the same world. And, indeed, it is a world saturated with media and technology. So, my learner already has a fairly sophisticated vocabulary, and reservoir of experience, to work with. They just need someone to believe in them, to give them a little nudge in the right direction, and a few conceptual tools that will allow them to find their own way.

For me, even if I have ideas mapped out and outcomes defined (learn about post-cinema through “Shoes”), it absolutely has to be up to my learners what they do with what I teach them because, “guess what?” These are just concepts that help us think about the world we live in. They are not the world we live. And they either work for you and have some resonance for you, or they don’t. That’s how concepts work.

I love the example of “Shoes” because it’s so memorable to so many people. It’s a memory of something they love or loved. And I don’t think that has to be reactive or nostalgic: to remember something you love in order for it to be useful in the present, including in a critical way. Sometimes images of the past have transformative power in times of overwhelming change.

In the class where I taught Muybridge this semester, I had several constraints.

1) I was assigned the course at the last minute.

2) It’s a lower division course (usually Freshman and Sophomores).

3) These are non-cinema majors (which is part of what I intentionally do).

4) I knew I wanted to make part of the focus of the course on post-cinema, but I also knew it would be a slow burn to get them there. I knew, right away, that I wanted to start with Muybridge (whom I teach in my San Francisco modernism class), and I knew I would do a section on melodrama as a way of teaching mise-en-scéne before I got to post-cinema. But I did not know ahead of time that “Shoes” would become part of this whole equation.

Let me ask you a question? Would you rather write a two page paper about “Shoes” or a two page paper about a 3 hour apocalyptic film starring Justin Timberlake? I think my students might choose “Shoes.” And I am more than happy to go along with them as we choose our own adventures together.

Affect in post-structuralism is not about feeling, per se, but the idea that there is no thinking without a-subjective experiences, encounters or relations with the world. Gilles Deleuze defines subjectivation as a fold. Or singularity. We are composed of all the external experiences, encounters, and relations we have had with the outside world as we have selectively folded or internalized them. No two people can ever be exactly the same—all bodies are substantively different—because no two people have ever had the exact same experiences, encounters and relations with the external world, with other bodies and the world, in the exact same way and, then, folded or internalized these experiences, encounters and relations in the exact same way. It’s a way of thinking the self as radically exterior (a-subjective) yet, also weirdly mediated through the senses (subjective). Immersed, if you will, in the world (which is, depending on how you think about it, kind of how it “works”). This is why it’s so great for teaching film.

According to this image of thought, all thinking, according to Deleuze’s idea of affect, is thinking-feeling.

These are huge ideas and I really only teach them in a casual rather than some ridiculous academic way because, once again, they are cool, they are interesting, but they are just ideas. And if you know the concepts well enough, then you can easily talk about them in a language that others can easily enter into.

[Note: Someday I want to write a scholarly article about instructional design and post-cinema, because all instructional design is post-cinematic.]

5. Mapping

Graphic: Fine Art Abstract Human Head by Danjazzia (licensed).

Let’s map “Thinking with ‘Shoes'” as a cognitivist instructional design.

1. The learning activity grabs the learners attention.

2. The learning activity is affective.

3. The ID activates thinking-feeling.

4. The video for “Shoes,” ironically begins with thoughts inside the various characters heads.

5. The video uses repetition and very few words. It is, itself a mnemonic device.

6. The ID uses memory to activate thought.

7. The ID uses something the learner already knows or is intimately familiar with in order to teach them something new or different, expanding their knowledge or thinking in their everyday lives out in the world (potentially about that world).

8. The ID activates problem solving. How do viral videos work? How do we think about the role of technology in our everyday lives?

9. The ID invites the learner to experiment.

10. The ID invites the learner to self-test or assess based on that experiment.

11. Assessment by the learner and the teacher is built into the ID.

12. This ID connects with aspects of constructivist and connectivist theories of learning.

6. References

Deleuze, G. Foucault. Paris: Editions de Minuit. 1986.

Deleuze. G. Pure Immanence. New York: Zone Books. 2001.

Shaviro. S. Post-cinematic Affect. London: Zero Books. 2010.

Solnit. Rebecca. River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wildwest. New York: Penguin Books. 2004.

Instructionaldesign.org. “Conditions of Learning (Robert Gagne)”. Website. https://www.instructionaldesign.org/theories/conditions-learning/. [Accessed 10/20/2019].

All graphics by the author unless otherwise noted.